-

Exposición

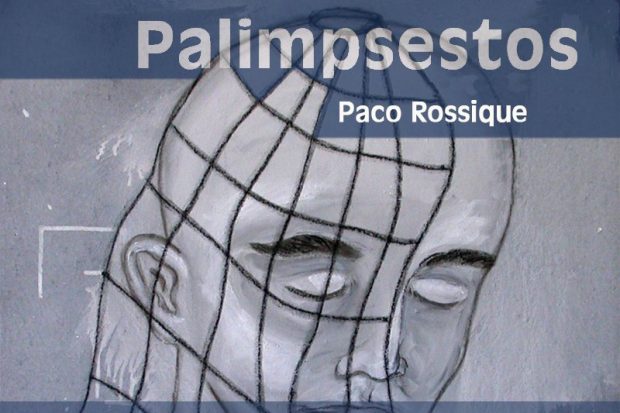

‘Palimpsestos’. Paco Rossique

30 septiembre > 19 noviembre 2016 Desde 1 €Acercarse al trabajo de Paco Rossique resulta al mismo tiempo de lo más sencillo y de lo más complejo. Si se acepta que uno de los elementos fundamentales en ese trabajo es el humor, – ese humor algo refinado, aquel que no suele provocar carcajadas-, se tiene ya un punto de partida para adentrarse en otros componentes, tal vez menos evidentes.No es imposible -pero resulta enriquecedor-, apreciar las pinturas de Rossique unidas a sus títulos. Y ello porque los títulos no tratan de explicar cada obra, al menos en el sentido más habitual del término, pero guardan una relación que de cuando en cuando parece más evidente, como para indicarnos que sí, que sigamos buscando.

¿Dónde buscar, por cierto? Si alguien tiene suficiente capacidad de penetración psicológica, puede intentar buscar la música en la mente del mismo artista. Se promete un viaje interesante, aunque cabe dudar que resulte especialmente clarificador, si es claridad lo que se busca. Porque aún estando esos títulos en evidente relación directa con cada pintura, resulta una tarea muy ardua discernir lo que hay en ellos de reflexión premeditada y de ocurrencia inmediata, intuitiva, tal vez ni siquiera racionalizada.

El conjunto se llama Palimpsestos y eso debe significar algo. Rossique ha recordado que los palimpsestos vienen de escribir sobre y entre líneas para aprovechar papiros o pergaminos, una práctica común en la Edad Media. Así, una obra de San Jerónimo podía escribirse sobre una de Cicerón, por poner un ejemplo. Esto puede ser literal en este caso, pero en esta exposición tiene un aspecto metafórico. No parece muy necesario describir las múltiples facetas de la metáfora que cabe imaginar en lo escrito sobre lo escrito. O, más etimológicamente, de lo grabado sobre lo grabado.

Lo importante no es siquiera si Rossique ha usado antiguos papeles para pintar, sino si ha pintado sobre algo inmaterial, sobre imágenes antes imaginadas, por ejemplo. No es nada imposible; en gran medida es algo que hacemos con cierta frecuencia, muchas veces de forma casi inconsciente. Reescribimos continuamente sobre nuestra memoria y también actuamos y creamos nuevos dibujos sobre otros que hicimos tiempo atrás. Nuestras neuronas son numerosas, pero no infinitas.

Éstas no son dudas que deban generar el estupor, que paralicen. Más bien indican que, sobre ese tenue pero seguro soporte del humor, podemos seguir lo que vemos, esas pinturas, con libertad para imaginar sobre ellas, aportando nuestras medidas y pesos corporales, nuestro conocimiento, nuestras experiencias. Podemos llegar a cualquier lugar que para Rossique es tan insondable como los mundos cotidianos que ha vivido el artista en su estudio.

No se ha mencionado la música. Curiosamente, para muchos que los escucharon a través de la radio, Palimpsestos, la música, fue antes que Palimpsestos, los cuadros. Es un poco como quien ha mirado el catálogo y no ha escuchado la música. Sin embargo, la música es importante, aunque solo fuera porque marca un tiempo, algo que los cuadros no hacen, pero sí el recorrido ante ellos. Ambos elementos, el visual y el sonoro, funcionan de manera independiente, como independiente es cada cuadro en el conjunto. Pero algo impulsa a sentir que la reunión de todo ello en una exposición es la que convierte a ésta en algo más que una sucesión de imágenes y de sonidos.

Approaching the work of Paco Rossique is at the same time both very simple and complex. If it is accepted that one of the key elements in this work is humour – a kind of refined humour, which does not usually make you guffaw with laughter-, we already have a starting point to venture into other, perhaps less obvious components.

It is not impossible -but it is enriching-, to appreciate the paintings of Rossique as attached to their titles. This is because the titles do not seek to explain each work, at least in the usual sense, but are related to each other and at times this relationship becomes clearer, seemingly to encourage us to keep searching for it.

But where should we look? If you have good psychological insight, you can try to find music in the mind of the artist. It will be an interesting trip, though it is doubtful it will be particularly enlightening, if you seek to be enlightened. The point is that, although the titles are clearly related to each painting, it will be very difficult to discern the deliberate reflection and immediate, intuitive, perhaps even rationalized, occurrence in them.

The set is called ‘Palimpsestos’ and that must mean something. Rossique has reminded us that the palimpsests were manuscripts on which later writing has been superimposed to re – use papyrus or parchment, a common practice in the Middle Ages. Thus, a work of St. Jerome could be written on one of Cicero, for instance. This may be literal in this case, but this exhibition has a metaphorical aspect. It hardly seems necessary to describe the many facets of imaginable metaphor in superimposing writing on existing writing, or, etymologically speaking, of recording on an existing record.

The important thing is not even if Rossique has painted on old paper, but if he has painted on something insignificant, on images previously imagined, for example. It is not impossible; in fact, it is something we do quite often, often almost unconsciously. We continually rewrite over our memory and perform and create new drawings on others from the past. Our neurons are numerous, but not infinite.

These are not questions that should generate amazement or stop you dead in your tracks. Rather they indicate with a light, but evident, sense of humour that we can follow what we see, these paintings, free to think about them, providing our measurements and body weight, our knowledge, our experiences. We can reach any place that is as unfathomable as the everyday worlds that the artist has experienced in his studio.

The music has not yet been mentioned. Interestingly, for many who have heard it on the radio, Palimpsestos the music was before Palimpsestos the pictures. It’s a bit like someone who has looked at the catalogue but not heard the music. However, the music is important, if only because it marks the tempo, something that the paintings do not do, focusing on the path before them. Both elements, vision and sound, work independently, as each frame is independent in the set. But we are impelled to feel that the collection of all of these in the exhibition is what makes it more than a succession of images and sounds.